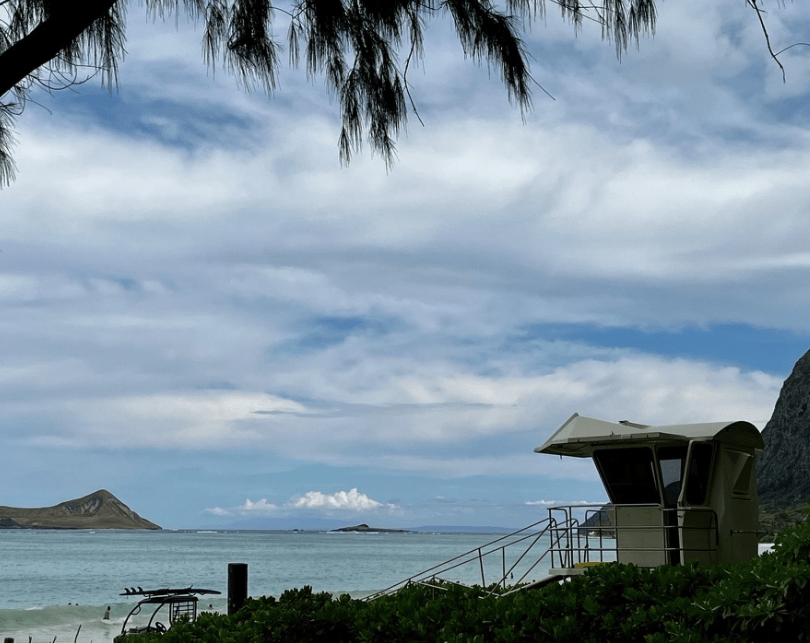

As we sample the many glorious beaches dotted around the island one can’t help but notice the ever-present lifeguard towers of O’ahu. Their distinctive character and unique surroundings add a certain charm to the stretch of ocean they serve. There are just over forty lifeguard posts on the island, each visibly numbered and equipped with jet ski, ATV, truck, and of course a retinue of trained, competent lifeguards. From the Windward and Leeward Coasts, to the famed North Shore and the string of the towers along Waikiki beach, it strikes me how vital the Ocean Safety Operations is to locals and tourists alike.

Our afternoon sojourn to the stunning Waimanalo Beach on the Windward coast is peaceful and serene, guards watching over a few body boarders playing in the surf. Tower 6A perches amongst a verdant and tenacious creeper that carpets the sand, light violet flowers adding pops of colour. The elements create a unique vignette in which the small, functional tower resembles a small house in a postage stamp garden. With 227 miles of coastline to oversee, the job of the lifeguards is to anticipate and ward off accidents, especially from those not taking the power of the waves as seriously as they should.

On another day we tour the island, reaching the renowned Waimea Bay on the North Shore. The beach has a long-standing tradition of surfing for native Hawaiians and now attracts big wave surfers from around the world, eager to ride waves that can exceed 40 plus. It’s a breezy, moody afternoon and as the waves crash wildly onto the steeply shelving beach, most of us are content to sit safely on the sand, taking in the scenery and marvelling at the power of the ocean.

An announcement blares from the tower… “hazardous conditions, people are a little too nonchalant out there, beware of the dangerous shore break which can lead to head, neck and back injuries.” The guard then implores, “You should only be out in the water if you have years of experience on this beach or with these conditions.” Only a few retreat to the shoreline.

Another lifeguard jumps on an ATV, riding to the far end of the beach where he reprimands a father for bringing his two young sons too close to the surf. Back at the tower, the guard steadies his binoculars, slowly sweeping his gaze across the outer waves. I had been told that thousands a year are rescued, that, ‘it’s a dangerous job in paradise for not a particularly great salary’.

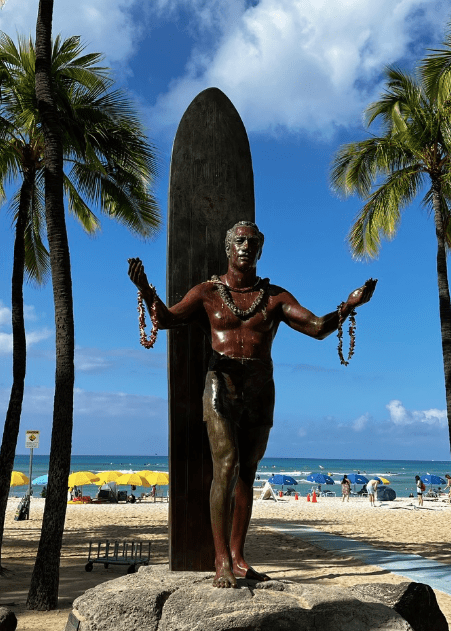

As on all beaches, a surfboard labelled ‘rescue’ in red letters is ready for action. It seems like an obvious method of rescue, yet it’s modern-day use traces back to the man who all Hawaiians revere, the father of modern-day surfing, Duke Kahanamoku.

Back on the Waikiki beach that pays homage to him, fresh leis invariably adorn the arms of Duke’s Kahanamoku’s statue. As surfers ride the waves and beachgoers soak up the sun just behind him, it’s easy to speculate that without Duke’s contribution to surfing, none of us might be enjoying the delights of Waikiki today.

As the graceful tufts of palms shadowing ‘Duke’ sway in the breeze, few, perhaps, of those who pass his statue understand just how compelling the story of surfing is, from the Beach Boys, to the journey of Hawaii’s iconic waterman.

In Hawaiian culture, a waterman is an honorific, a proud distinction for someone who is fully in tune with the trade winds, the tides and the ocean. A waterman knows how to paddle, surf, sail, and swim. Not only was this title bestowed upon this beloved son, of pure Hawaiian ancestry, but Duke would become a five-time Olympic champion, the father of modern-day surfing, a Hollywood actor, a sheriff, a nightclub owner, and most of all, an esteemed lifelong ambassador of Hawaii.

Born on the island in 1890, Duke’s family moved to the Diamond Head area of Waikiki during his childhood. His mother’s family owned a plot of land amongst the rice and taro paddies. Julia was the daughter of a high chief from Kuai, and married Duke Halapu Kahanamoku from Maui. For the eight children, the Waikiki beaches were their playground.

Duke became a masterful swimmer and surfer, fashioning his own surfboards from enormous planks of Koa wood that could easily weigh 125 pounds. Lugging the boards was cross-training in itself, but this had long been a way of life for Hawaiians. In 1777, a surgeon aboard James Cook’s ship, The Resolution, journaled of native Hawaiians surfing and the ease in which they did so. By 1847, missionary H. Bingham deemed it a ‘heathen sport’ primarily as it encouraged the intermingling of the sexes, not least as they were barely clad! The missionary also opined ‘that surfing diverted Hawaiians from honest labour’ and spoke disparagingly of surfing as the ‘pastime of chattering savages.’ By 1900, with the arrival of more and more missionaries and settlers, as well as laws and social standards discouraging Hawaiian cultural practices, the noble and traditional art of surfing was in a sad decline.

In 1900, when Duke was ten years old, Hawaii unwillingly became a colony of the United States. Eight years later in a reaction to the whites-only Outrigger Canoe Club, Duke and two others formed their own club, mostly comprised of full or partial Hawaiian-blooded locals. Ostensibly for swimming, the club evolved to include surfing, canoeing and kanikapil… the impromptu style of local music, ideally performed on the beach. The Hui Nalu (Club of the Waves) was based at the Moana Hotel and became a hotspot in Waikiki. In 1915 when some of the members started beach concession businesses, they contributed to the unlikely beginnings of the renowned Waikiki Beach Boys.

Visitors were mesmerised by the prowess and talents of the Boys on the water. By the late 1920’s, they became constant companions, tour guides and friends to the well-paying visitors. Lessons were given in swimming, surfing, canoe wave riding. Musical evenings rounded out the local experience. And even as the Beach Boys earned good money, they had the pleasure of being in the water and proudly sharing the heritage of their island. Duke Kahanamoku would go on to exemplify what Beach Boys even today emulate… the Ambassador of Aloha.

When the US Mainland held an outdoor swim meet in Hawaii in 1911, Duke easily set two World Records in the 50 and 100 meters. Yet when the results reached head office back in New York, the records were rejected… “it’s only Hawaii, so far away, no oversight,” etc, etc. Hawaiians reacted to the snub, and likely to the racism, by rallying to pay for Duke’s passage to the mainland to compete for a spot on the Olympic Team. Few people had been to Hawaii, nor could find it on the map, and Duke appeared as an anomaly… an Islander with a powerful physique and technique, bestowed with grace in the water, with humour and good sportsmanship. Duke was selected for the US Swim team and the story thereafter only burnished the legend. Gold and silver medals in Stockholm, 1912. Two golds in Antwerp, 1920. Silver in Paris, 1924; his brother Sam won the bronze!

Duke’s fame opened many doors in the US and around the world as he promoted surfing. At this time, home was California where he became an active member of the LA Athletic Club, mingled with movie stars, eventually becoming an actor himself. Signing with Paramount Pictures, Duke would have roles in some twenty movies, invariably relegated to playing ethnic parts. Teaching and spreading the art of surfing remained a constant in his life and in 1925 when a fishing boat capsized in Corona Del Mar, California, respect for the Olympian increased even more dramatically. Through 25 foot waves, Duke bravely paddled out to the drowning victims, rescuing three at a time on his surf board. That day, eight people owed their life to Duke’s bravery and when the rescue made the headlines in big city newspapers, his fame as a national hero was truly cemented. The ‘rescue’ surfboards we see on the beaches of Hawaii today, are just one of his legacies.

After failing to make the Olympic team for LA in 1932, Hawaii tugs at his heart and Duke returns to O’ahu. He still travels and is feted around the world, yet once he’s returned to his roots he questions ‘what’s next?’ In 1934 Duke is elected Sheriff of Honolulu which he serves for twenty-six years and while doing so, the world discovers tropical paradise on the islands and the ‘famous sheriff of Honolulu’ finds the time to play host and entertain the rich and famous. Meeting Duke was a must!

In 1940 Duke married the love of his life, Cleveland born Nadine Alexander. The ballroom dance instructor had noticed the Hawaiian legend in magazines and once established on the island and teaching dance at The Royal Hawaiian Hotel, she reported that her first meeting with Duke was love at first sight!

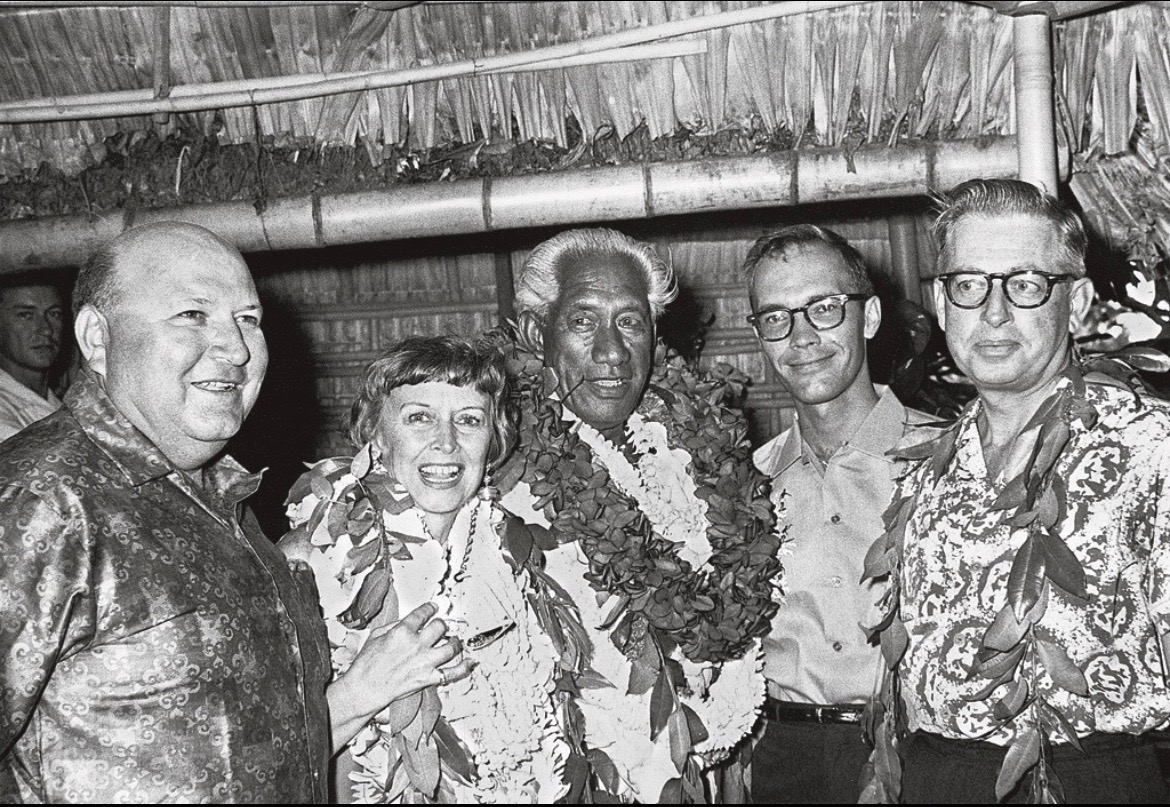

I can only imagine the delight when at age 71, Duke starts yet another career as owner of Duke Kahanamoku’s Club in 1961. The clubs impressive entertainment lineup, eventually including the legendary Don Ho, made it the hippest place to be seen.

Tiny paper umbrellas completed the mai tais. Crisp whites or florals, complimented by a lei, was the sartorial choice for all. And hula dancers performed to hapa-haole songs under the glow of tiki torches. Stars like Judy Garland popped in to perform. Sammy Davis Junior or Tom Jones could be seen in the audience, and watching from his peacock chair was Duke himself greeting friends and posing for photos. The golden age of tourism in Waikiki was underway and the Duke Kahanamoku Club was at the heart of it all.

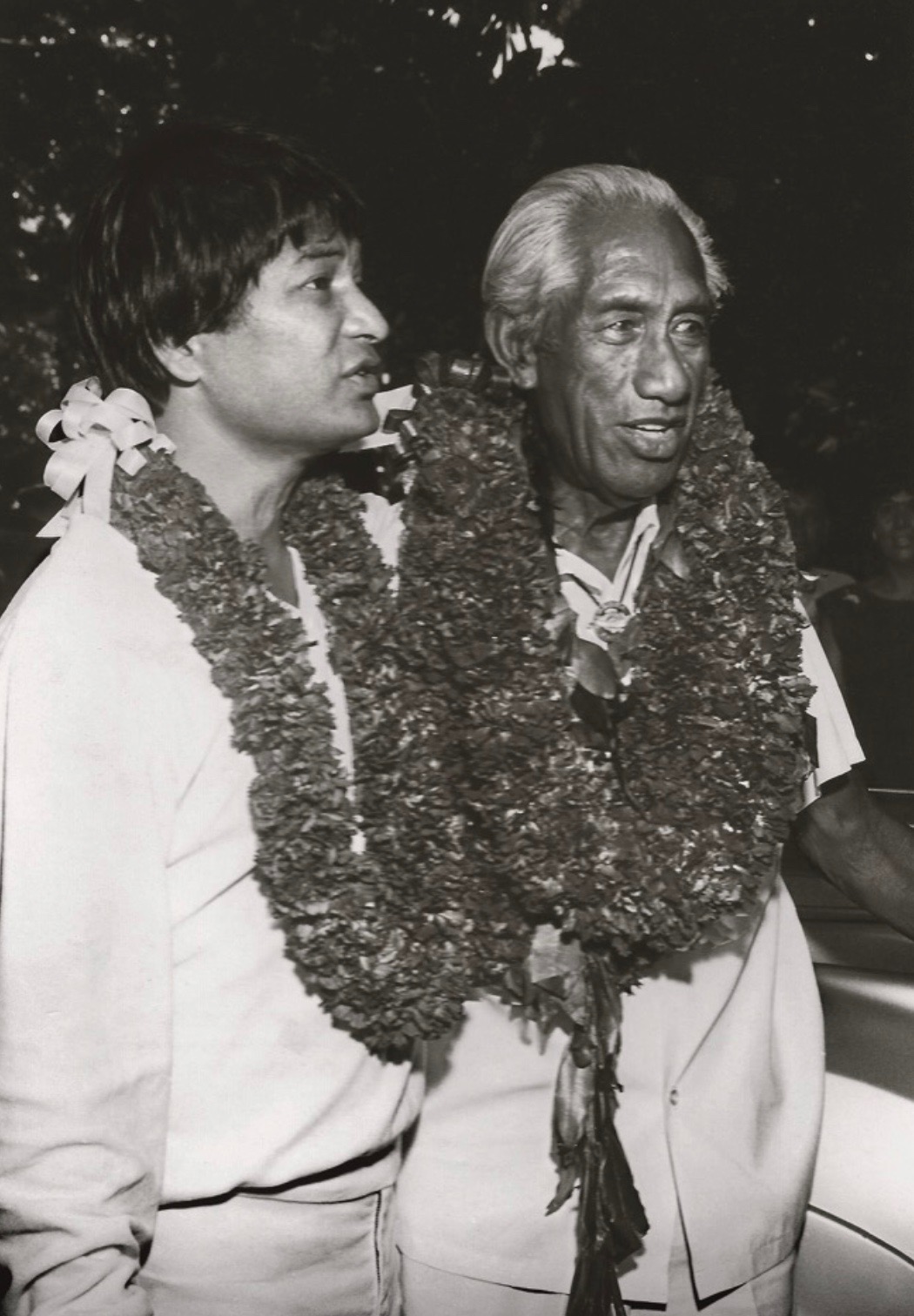

Through the years, Duke stayed very much connected with surfing and when it became the sexy image of Hawaii’s tourist boom, stars like Elvis, Rita Hayworth and Gidget helped popularize the islands. Shows like Hawaii 5-0 and Magnum PI followed. When Duke passed away in 1968, even with all the varied facets of his life, his life was celebrated by a massive Beach Boy funeral on Waikiki. Paying the deepest respect to Duke Kahanamoku’s love for the sea, his ashes were cast into the ocean from an outrigger canoe. His legacy as the touchstone of ancient Hawaii to the modern era of surfing, as a racial pioneer and Olympian, as Hawaii’s most beloved son was celebrated and honoured.

As I researched this piece, I came across an episode of ‘This is Your Life’. Duke is perhaps in his 70’s and being honoured for his life’s work. Each mystery guest places a lei around his neck as they enter the stage, then a handshake, a hug. Three of the men that he had rescued are there, they thank Duke for their life which he accepts humbly. He is charming, and warm taking it all gently in his stride. A few of the surviving Beach Boys pay their respects, as do his siblings, proudly reminiscing, then filling the stage with harmonious songs of Hawaii. Then Nadine enters the stage, pretty and graceful in a floral dress and a bespoke lei. She’s dainty beside her strong, imposing Duke, layers of leis around his neck now almost obscuring his still-handsome face. Nadine’s wrist jangles as shy places her hand over his. She isn’t shy in admitting that it’s his Olympic medals dangling on her wrist. Their love radiates through the black and white screen and I can only imagine what a time these two had at their Club – the darlings of Waikiki, dancing the night away.

Duke’s life makes you smile… a life well lived, a proud Hawaiian legacy, a poster boy for these islands that I came to adore. If you stroll past Duke on the way to the beach, give him my fondest regards!