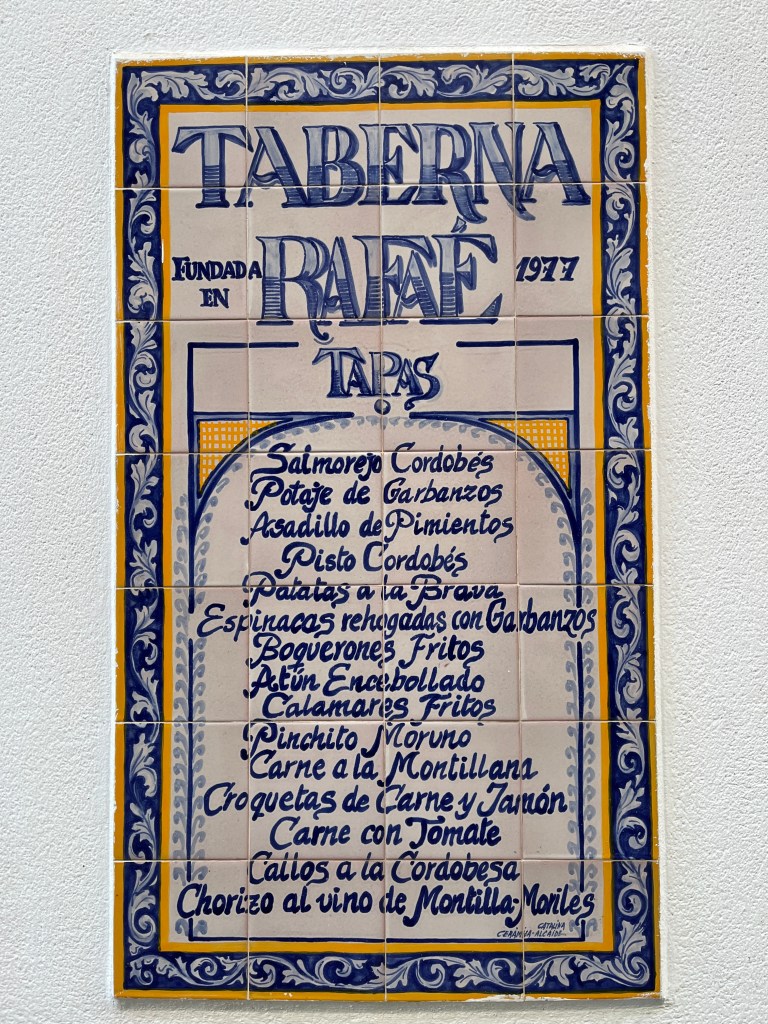

The Le Taberna del Foro is lively and crowded. It’s Friday evening in Madrid and a three-hour flight from Edinburgh lands us in time for drinks and tapas. We slide into a tiny table for two near the pie-shaped bar, lined adoringly with as many books as wine bottles. I order a glass of secco blanco, Bruce decides on a vino tinto and we expectantly unfold the pristine map of Madrid… the promise of a colourful canvas of streets and architecture, of life out to all four corners, a new city for us both!

After having checked into out hotel near Madrid Atocha, the main train station, we haven’t wandered too far into the surrounding charming neighbourhood. I admit to having felt a little overwhelmed by the thought of this capital city, conveniently situated in the middle of Spain, yet at once it feels familiar in its obvious elegant grandeur. We pour over the map noting the iconic sites – those must visits in any city – yet for us it’s more about the outlaying neighbourhoods, the barrios which give all Spanish cities their unique character.

Saturday morning beams sunshine and warm temperatures for mid-November. The crowds are tremendous with locals, Spanish day trippers, tourists alike, and not surprisingly! This is the political, economic and cultural centre of the country with the second-largest GDP in the EU. Madrid is an iconic city and of course we beeline up the Grand Via to visit the landmarks – The Royal Palace and Almudena Catheral, Plaza Mayor, Puerto del Sol. The grand central square is an enduring symbol of the city and resplendent in century-layered architecture. Originally a bustling market, the plaza has also hosted bull fights, royal ceremonies and tragically, trials during the Spanish Inquisition. King Philip III sits atop a bronze equestrian statue paying homage to the reach of Spain in the late 1500’s… Kings of Portugal, of Naples, of Sicily, even Lord of the Seventeen Provinces of the Netherlands. The Philippines, a former Spanish colony, is named after Philip’s father, the II, also known as Philip the Prudent.

With the main sites orientating us, we stroll. Like the Italians, the Spanish love to perambulate their calles; always well dressed, well perfumed and with animated conversation. We meander, seemingly traversing the entire city that day. We leave the busy Gran Via for the intimate neighbourhoods of Salamanca, Lavapies, La Latina and more. The narrow streets are flourished with petite intricate wrought iron balconies, muted pastels and cozy tree-dappled plazas dotted with neighbourhood tapas bars. We chance upon a rose garden still abloom, quiet calles of towering cyress trees, pigeons frolicking in marble fountains, local gossip mingling with strains of classical guitars… all touchstones of life in this grand, yet surprisingly intimate city.

By 7 pm, we chance upon the smallest of bars with rickety vivid-green tables and a tapas menu that I’ll dream about for years. Alas, the kitchen doesn’t open until 8 so we have no choice but to order a bottle of roja and relive the day. Seventeen kilometres of bliss, excellent local food here and there, and admittedly because of the beautiful weather we hadn’t been enticed to join any inside tours. Just a spectacular day of soaking up the essence of Madrid.

“If Seville is a gentle Spainsh guitar tune, Madrid is a full-on flamenco dance,” I muse to Bruce. I fell in love with Seville on a previous trip and ideally one should visit both. If crowds and distances are difficult for you, Seville will give you all the flavour you need, yet the transportation system in Madrid is efficient and accessible. My feet are worn out so we plot tomorrow’s endeavours with a slightly slower pace, which we both agree must include The Prado Museum!

The Prado Museum is what the Louvre is to Paris, the British Museum to London, the Uffizi to Florence. Before losing yourself in the Prado, first wander its environs as the museum is nestled on the edge of the grand El Retiro Park. And the Retiro is to Madrid what Central Park is to New York City, what Hyde Park is to London, or Stanley Park to Vancouver… parks that are the breathing lungs and oases of calm. El Retiro is just that, a sprawling Unesco World Heritage Site, a former royal park with 19,000 trees, art galleries and a lake. Opened to the public in 1868, one can stroll, row, pedal, play tennis, or enjoy a picnic in the grounds.

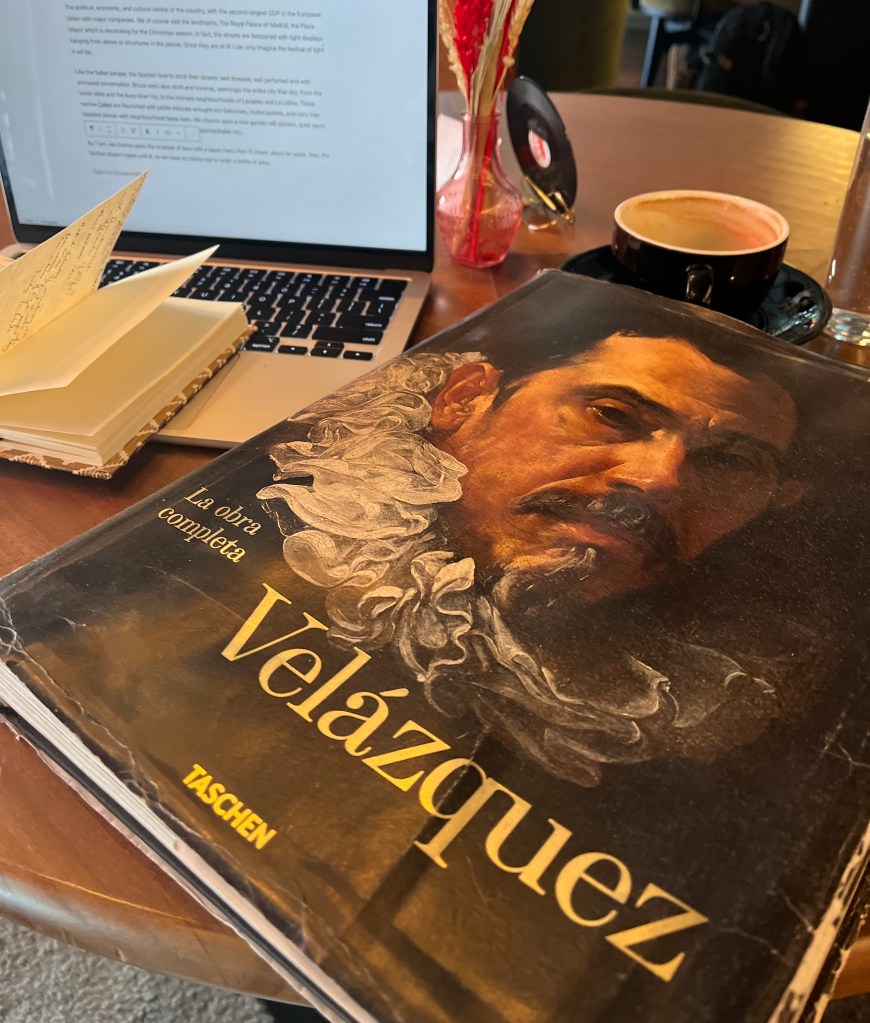

I absolutely adore museums of all kinds and like markets in a city, museums are also the touchstone of its citizens… the guardians of art and history, of a people’s story. The building that today houses the Museo Nacional del Prado is a splendid work of art in itself. Designed in 1785, it is sprawling, stately and the custodian of some 2300 paintings. The predominate mood is that of Tenebrism – dark, gloomy, mysterious – common of Baroque paintings and Diego Velazquez did this exceptionally well. A leading artist in the court of King Philip IV, the museum holds a vast collection of Velazquez’s celebrated paintings with Spain’s dramatic history coming alive on the evocative canvases. Masterpieces from Titian, Goya, Raphael and El Greco also regal the walls, testament that The Prado has certainly evolved since it opened in 1819 as a Natural History Museum.

Late the next morning we hop on a Renfe train to Toledo, barely an hour’s journey south-west. A short walk from the train station reveals the ancient city nestled along the Tagus River. This World Heritage Site by UNESCO is immediately dramatic. Perched imposingly on a hilltop for defense purposes, it calls itself the ‘city of three cultures’ – Muslim, Christian and Jewish. All of their architectures still a mosaic of hues, cobblestones and ancient wooden doors. The Archways of the Alcazar welcome you in.

The Romans called this Toletum, incorporating it into their empire after a battle with Celtic tribes in 193 BC. This town of non-citizens is where one could obtain Roman citizenship in exchange for public service, and build they did! The Roman circus – an open-air venue for chariot races – along with an amphitheatre was one of the largest in Hispania, once the name for the Iberian Peninsula and now part of Spain. The circuses teemed with public entertainment to keep the population content and to prevent unrest. Many of the new citizens would have also helped build splendid villas for wealthy elites in the 3rd and 4th centuries as the city became a literary and ecclesiastic centre well into the the mid 700’s.

Toledo also became a major cultural centre promoting productive cultural exchanges between the Islamic world and Latin Christendom. Its long history of bladed weapons production and glass manufacturing is still evident as you wander the quiet streets into the old quarter. Winding cobblestoned lanes harken to a celebration of cultures and religions, each giving the city a rich architectural and artistic heritage. Today the city celebrates the harmonious living between Muslims, Jews and Christians alike.

We happily dine in an Arabic restaurant, we savour the evening dusk and then the illumination of Toledo’s architectural wonders. It’s now eight in the evening, the streets and plazas begin to fill for evening strolls. For us, it’s time to catch the train back to Madrid. Time to savour the joys of jumping on a train. Time to plot tomorrow’s adventure!