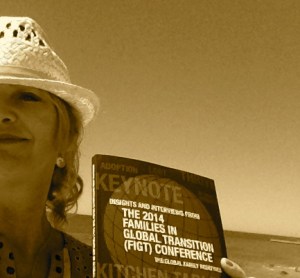

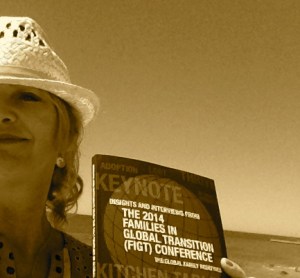

I unwrapped it expectantly. It had been awaiting my return to Canada, top of the mail pile. I’ve had magazine articles published before, but this is the first time to have articles in a book, Insights and Interviews from the 2014 Families in Global Transition, (FIGT).

I unwrapped it expectantly. It had been awaiting my return to Canada, top of the mail pile. I’ve had magazine articles published before, but this is the first time to have articles in a book, Insights and Interviews from the 2014 Families in Global Transition, (FIGT).

In fact my first blog post, written about a year ago, was penned after returning from that conference in Washington. I had been one of the eight writers, tasked with documenting the insightful lectures and talks. Many long hours of writing and editing later, I submitted my work, only now seeing the finished compilation. Of course, it’s a grand feeling.

And it’s timely, as next month we come to the end of our posting in Kazakhstan. This is exactly what FIGT concerns itself with; transitions, culture shock, ‘third culture kids’ (TCK’s), identity loss, and the many issues that families face as we relocate worldwide or even within one’s own country. I feel the usual trepidation, yet excitement as the next move looms. In just over a month or so, I will live in another country, likely a different continent. I will pick up and follow my husband… I am a ‘trailing spouse’.

And yet ‘trailing spouse’ is a term I don’t embrace. It suggests a lack of purpose, identity, lack of choice, which are all true to some extent. This post is dedicated to those of you who, like us, live an international lifestyle or for those contemplating setting off across the seas to explore. For those of you who don’t live the expatriate life, I beg your indulgence to take a little glimpse ‘under the hood’ of the whole thrilling enterprise, yet also into the more mundane and sometimes alarming aspects of this life we hold dear.

Bitten early by the travel bug

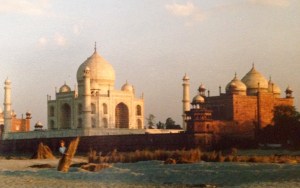

I was bitten early by the travel bug; trips to Europe and then to Thailand confirmed my love of exotic places and an urge to wander. I met a Scottish guy who shared my passion. He rolled into Calgary just before the ’88 Winter Olympics. Our first date was to a travel show about Africa and a year later we were backpacking through Thailand, India, Nepal and China before settling in Japan, and why not? It was a magical time.

We taught English and reveled in the young western ‘Gaijin’ crowd that occupied Osaka and Kyoto. We embraced this lifestyle with open arms just as we embraced each other, got married and started a family…and ventured onto an unknown path.

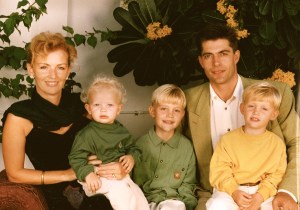

Our first home was in The Netherlands and we kept going from there; mostly, it’s been an exciting adventure, a privilege all these countries later. Yet the seemingly effortless mechanism that allows us to glide between borders has on many occasions been exposed to reveal a trying and more complex reality. And then you add raising kids to the equation.

This expat life is a lifestyle choice that only works well if it’s a partnership, if the spouse that ‘trails’ is happy, or at least content. An acquaintance of mine asks me. Does hubby know where he’s going yet? Well it really isn’t just hubby (who works for an energy company), it’s both of us that will once again adjust to a new life.

True, it doesn’t seem as complicated these days. No need to arrange schooling in the next country, worry whether the move coincides with junior or senior high. No need to feel guilty for taking the kids away from friends, yet again. Won’t have to say goodbye to countless families that we camped and boated with, traveled to hockey tournaments with, dined and danced with at villa parties until the wee hours of the morning. These friends became family because we were all without our own, raising our young children and teens together. Oh those were glorious years.

Yet with that phase behind us, the pending location still impacts our life and even those of our now adult children. Will it be somewhere we can see them more often and other family as well? Is it a place they could come visit, Kazakhstan wasn’t exactly an easy location to welcome visitors! I’m fortunate that I jump on flights and make it home for family occasions despite living here, yet the long haul flights are wearying with jet lag at either end. No, I’m not complaining about the excursions I enjoy along the way, I know I’m lucky. So perhaps in that sense, I’m not a ‘trailing spouse’. Am I not that travel companion I always was, from the beginning?

Yet with that phase behind us, the pending location still impacts our life and even those of our now adult children. Will it be somewhere we can see them more often and other family as well? Is it a place they could come visit, Kazakhstan wasn’t exactly an easy location to welcome visitors! I’m fortunate that I jump on flights and make it home for family occasions despite living here, yet the long haul flights are wearying with jet lag at either end. No, I’m not complaining about the excursions I enjoy along the way, I know I’m lucky. So perhaps in that sense, I’m not a ‘trailing spouse’. Am I not that travel companion I always was, from the beginning?

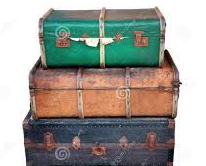

And even the relative ease of this upcoming move seems too good to be true, at least in the physical sense, almost like back in those carefree days of backpacking. I arrived with luggage, ‘only luggage’ stuffed with as many books as possible. The usual relocation of furniture and household effects didn’t pertain to this posting. No this time there’s only memories and a few other ‘intangibles’ to pack away.

So what’s the problem then? Well, we do have a say in where we choose to relocate next, but the final decision isn’t ours, so to speak. And as any expat will admit to you, while you’re waiting to hear your ‘fate’ you tend to get a little nervous. And even though you’ve done this umpteen times before, half of you wants to fly home and lock up your passport.

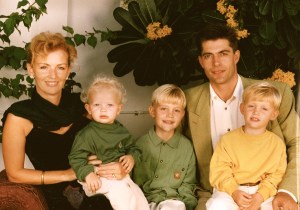

Our young expat family

And so I ponder the options…yes in a few of the locations I already have friends there, true some countries are closer to home than others, indeed the climates and cultures vary drastically… literally options around the world. And that’s when the other half of me gets excited.

Back to that problem? Will it be somewhere that I can inhabit happily; a true ‘home away’ from home. This short posting was anything but that and yet I believe I made the most it. But I now have a list of what I’d also like in country X; a writer’s community, an inspiring place to write and to host more writing workshops and hopefully a treasured circle of friends.

But the real clincher… please let me I’ll feel like I’m not wasting these precious years by living in a place that doesn’t gel, just doesn’t work. If you’ve committed to a 3 or 4 year assignment and it doesn’t work, well that’s when I’ve seen women fly home, kids in tow and not return. That’s when depression can set in, when marriages might fail, when one despairs. What on earth have we done!

Thankfully in retrospect, all of our locations ultimately succeeded, often beyond our expectations. But It was our move to Houston that brought me back down to earth; perhaps the first crack in my ‘idyllic expat wife veneer’. For the previous seven years, I had happily taught ESL whilst living in the Middle East. It was part-time and ideal in many ways as I still had time with our sons. I started the ESL program at the British School in Oman and taught children from around the world. I tutored a young prince from the Qatari Royal Family who loved to bring his prized falcon to class. I taught adults who were delightful and showed their appreciation with gifts of incense and silver. I adored it.

And then the axe fell, so to speak, with that move to Texas. A threatening stamp in my passport reminded me that I was not allowed to work. The irony of it all; there I was back in North America after 14 years abroad and I couldn’t work. Despite being busy with three children and yes, many wonderful times, an identity crisis crept in.

At the aforementioned FIGT Conference, one of our writers in Insights and Interviews, Cristina Bertarelli, interviewed Evelyn Simpson and Louise Wiles. They’ve created a company that focuses on, ‘Decide to Thrive’, which supports accompanying partners with the ultimate goal of ‘Discovering Global You and Empowering Global You’.

At the aforementioned FIGT Conference, one of our writers in Insights and Interviews, Cristina Bertarelli, interviewed Evelyn Simpson and Louise Wiles. They’ve created a company that focuses on, ‘Decide to Thrive’, which supports accompanying partners with the ultimate goal of ‘Discovering Global You and Empowering Global You’.

Simpson and Wiles discovered that there is a clear connection between an active working partner and a successful family relocation. A survey revealed “that despite 78% of participants saying they wanted to work whilst they were living abroad, only 44% were doing so and of those only 16% were working full time. Our findings also showed that higher percentages of people who were working reported high levels of life satisfaction and fulfilment versus those who were not working.”

Yet Simpson and Wiles also remind us that many expat wives are happy to have a career break and focus on families. However, the survey concurred with the situation that I soon experienced myself in Houston. A long term quest to find something that was going to sustain me going forward. During those six years, I now realize that I truly felt like a ‘trailing spouse’ and often bemoaned my fate. It wasn’t just me. Off the top of my head, I think of my friends around the world who sacrificed their careers to follow their partner. They are doctors, psychologists, nurses, engineers, accountants and teachers.

Some of these friends lament that their qualification doesn’t apply to their present country or after a break, it’s a challenge to return to their  profession. And often that’s accepted as we happily live life, raising families and supporting husbands. In many cases we may have homes to take care of in different countries with endless flights to book, schedules to organize. We require flexibility to travel at any time for a family event or an illness. It all gets incredibly busy and then one day you realize your path has meandered down a side trail and albeit a very interesting, colourful road that you’re pleased you traveled along. But that original path is gone, now what will you do? Especially if you find yourself in a country you had no intention of living in, as I did with Kazakhstan.

profession. And often that’s accepted as we happily live life, raising families and supporting husbands. In many cases we may have homes to take care of in different countries with endless flights to book, schedules to organize. We require flexibility to travel at any time for a family event or an illness. It all gets incredibly busy and then one day you realize your path has meandered down a side trail and albeit a very interesting, colourful road that you’re pleased you traveled along. But that original path is gone, now what will you do? Especially if you find yourself in a country you had no intention of living in, as I did with Kazakhstan.

In our book, Insights and Interviews, another of our writers, Justine Ickes, interviews Linda Jansen, author of The Emotionally Resilient Expat. Linda sums it up concisely.

“We undertake momentous transitions as we cross culture. It is those transitions and change which bring opportunities, struggles, enriching gifts, difficult losses, but above all they bring growth. It’s up to us whether to choose to embrace this growth as positive or negative.”

Agreed, and indeed we are often more resilient and resourceful than we give ourselves credit for. We volunteer, serve on school boards, organize and coach sports teams or teach other pastimes, study, gain languages and learn new skills. I became a tour guide in Norway and studied Viking history. I now can also add kayaking and cross-country skiing to my list of new pastimes from our years there. The salsa lessons didn’t work out that well for me! In short, I along with many of my friends, embraced Norwegian life. It made all the difference.

But back to that arrival in Houston, if only to remind us that there are times when we all face difficult challenges, wherever we may be. To encourage us that we can make our way out of that dark ‘tunnel’, it just might take time.

I recall arriving at my children’s new school for the first time. I looked out to an auditorium of strangers. I remember feeling dread, despair. Not one person did I know, not a familiar face, never mind a friend. I’ve got to start all over again! Every day for those first months I wanted to flee, back on a flight to Oman which had been our home in every sense.

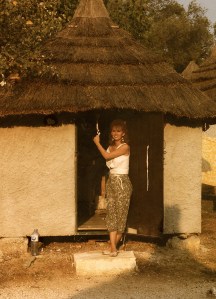

One of those magical holidays

When we relocate, the husbands (or wives as there are also male accompanying partners) continue with work in the new location, the children start school and then it is up to those of us who accompany to find a way to adjust. If it’s a new country, we figure out where to shop, perhaps get a new driver’s license and maybe learn how to drive on the other side of the road. We decorate yet another home, find new babysitters for our kids, and very importantly, hope to forge new friends.

Four months after we moved to Houston, I went to a ‘Yay! The Kids Are Back In School’ coffee morning. A Scottish lady with a stylish hair cut was introduced to me. “How long have you been here? Where were you before this?” The usual questions we expat wives invariably begin first conversations with.

It seems we were best friends waiting to find each other. And we now had, in each other, someone that understood our transition woes. After years in Indonesia, Gillian was also struggling with culture shock. The two of us walked and talked our way through those first years in Houston; you always feel you can go forward with at least one good friend.

Part of me also knew I had to integrate and feel useful. A month or so after the move, I found myself on a baseball field on a humid evening. I had signed up to coach my youngest son’s baseball team. After all I had set up a league in Oman and coached for years. Yet I had almost backed out. We had been at a welcoming neighbour barbecue and I had mentioned that I would be coaching the upcoming season. There was almost stunned silence.

“Y’all know how serious these Texan fathers take their baseball, haven’t seen a woman coach before.”

I’m pleased I went through with it. Halfway through that first practice, I walked over to address the parents. I shan’t forget her, Penny was her name. She looked out to me and spoke on behalf of the parents, “Ms. Terry, we’re all just sittin’ here praisin’ your name!”

In true Texan fashion, I was welcomed with open arms. Maybe it was going to be just fine after all.

Relocating is a challenge and often demands all of our resources. But whether it’s through volunteering, working or studying we integrate, re-define or even re-invent ourselves. For those who embrace change, there are many varied and colourful moments as an expat; days when you pinch yourself, life is just so great. But the peaks of emotion can be steep and the lows incredibly deep without family close at hand, with language and cultural barriers, with continuous farewells to friends. And when they jet off to the next location, you don’t want to be left behind; the proverbial ‘itchy feet’ syndrome sets in.

Relocating is a challenge and often demands all of our resources. But whether it’s through volunteering, working or studying we integrate, re-define or even re-invent ourselves. For those who embrace change, there are many varied and colourful moments as an expat; days when you pinch yourself, life is just so great. But the peaks of emotion can be steep and the lows incredibly deep without family close at hand, with language and cultural barriers, with continuous farewells to friends. And when they jet off to the next location, you don’t want to be left behind; the proverbial ‘itchy feet’ syndrome sets in.

In one of my articles in Insights and Interviews, I write, “The trials and difficulties we experience as expats are often not discussed or fully appreciated by non-expats. My mother has often defended my ‘privileged’ life by asking people how they would cope with finding new schools, homes, doctors and friends every four years or so. More often than not, the response is that they had never really considered any of that.”

As time passed, I found ways to compensate for the fact that I couldn’t work. I mentored high school students who were in distress and know that I made a difference in their lives; an opportunity I wouldn’t have missed. I took a few evening courses and yet time was ticking. I would question, what do you want to do with the rest of your life?

After six years in Houston, we relocated to Norway which eventually would be a catalyst for the  ‘good place’ I feel I’m in today. Jo Parfitt sums it up in a book she co-authors, the very useful and successful, A Career in your Suitcase.

‘good place’ I feel I’m in today. Jo Parfitt sums it up in a book she co-authors, the very useful and successful, A Career in your Suitcase.

“A portable career is work that you can take with you wherever you go. It is based on your unique set of skills, values, passion and vision and is not based in a physical location.”

As if she were speaking to me directly, Jo summed up my situation. My time in Norway is when I was finally able to meld my passions and talents, finally culminate them into the start of a new direction; a readjustment. But it isn’t just us accompanying partners that must continually adjust, it’s also our children, those TCK’s.

Our writer, Dounia Bertuccelli, addressed this when she covered a session at FIGT. She knows the trials of being a TCK, having lived and studied in 7 countries herself.

“By the time they are 18, most TCK’s have said goodbye to many people and places. Sometimes they were leaving, other times they watched friends move away. At International Schools students must regularly cope with the emotional upheavals of leaving…”

I shall never forget the sorrow of my 17 year-old in Norway as he arrived home after saying goodbye to his first love. We were moving, they had no choice in the matter. As a parent, all one can do is hold them…and be thankful that time heals. Yet does it completely?

The writers at the 2014 Families in Global Transition Conference with our leader, Jo Parfitt

Our well rounded, seemingly adjusted son would handle the transition from Norway to his home country of Canada far worse than we anticipated. He had visited every summer and Christmas, but had never lived there.

Sue Mannering, one of our writers currently living in Singapore, covered a FIGT session led by Danau Tanu, a TCK that has written a thesis regarding the topic of “Where are you from?”

Sue wrote, “How do you answer ‘Where are you from?’ The answer might be how much time do you have?”

I remember waking up one morning at our cabin a month or so before my son was to start University. He had come across a blog that a young TCK had written about not knowing where to call home. My son had forwarded it to me with the title…This is me Mom, where do I call home??

He was reaching out as he tried to cope, figuring out how to go forward… distressed. Seemingly those experiences and friends that he missed from a life abroad, now had to be tucked away from his identity. As expat parents we are continuously questioning our decisions in this lifestyle…should we have moved sooner so they could have had a home town, what if their academic skills don’t translate, do they feel like they have roots, how will we forgive ourselves if they come to us one day and suggest we ruined their life for ‘dragging’ them around the world?

New horizons and our FIGT compilation

You remind them of those magical holidays, the experience of people and cultures, the opportunity to play in sport tournaments throughout Europe, etc, etc. I have heard it time and time again from parents. We want to believe we’ve given them a good life, yet seem to also second guess this privileged life of travel and private schools. We want to believe they’ll just plunk themselves home when the time comes and all will be well.

As partners, our emotional well-being can often end up taking a backseat as we help our children transition. And yes, this can go on into the University phase as was the case in our family. That morning after reading my son’s email, I hastily made my way back to the city. He needed counselling and three hours later, he understood that he needed to embrace all of his life experiences and proudly acknowledge his international past.

And that is essentially the key. Whether it be our children or as an accompanying partner, we must endeavour to… well, one of my lovely Texan friends gave me a handcrafted tile before I left. It summed it up beautifully, Bloom where you’re planted.

So thrive and grow, some days it’s far easier than others. Those difficult days have to be accepted and put away. Our TCK’s need to be re-assured that they will find their path and like us, a small piece of their heart always be waiting for them in the countries that they’ve lived…and with friends that they’ve loved. Thankfully there are now many resources available to us for support, such as FIGT and their links; even our newly published book that we are all proud of.

So I shall soon know where I’ll next be ‘planted’. And one more requirement now that I think about it, is to live somewhere that I can easily get to the 2016 FIGT Conference, next March in Amsterdam. And I encourage expats to consider being there. You will be enlightened, inspired and make new friends, as I was, and most certainly did.

Jo Parfitt summed it up in the forward of Insights and Interviews, “Here are the people who know the answers. The experts, the gurus, the leaders. This is where people ‘get me.’ It has often been said of the event that it is a place where ‘best friends meet for the first time.'” Then again, you can be sure I’ll be there, no matter where I am in the world.

As I checked into the Calgary Airport for the trip back to Kazakhstan this past visit, the Air Canada agent noticed my luggage as I heaved it onto the belt. I myself had my eye on the scale, hoping it wouldn’t be overweight yet again.

As I checked into the Calgary Airport for the trip back to Kazakhstan this past visit, the Air Canada agent noticed my luggage as I heaved it onto the belt. I myself had my eye on the scale, hoping it wouldn’t be overweight yet again.

“That’s a fine set of luggage you have there, Ms. Wilson.” I chuckled a thank you.

But what I was really thinking was…Yes and there’s more packed in there than you’ll ever know. My ‘wee career’, my resilience, my wanderlust, my friendships, a photo of those precious sons with that traveling partner that I’m more than willing to accompany….wherever it may be in this big, frabjous world. And no, I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Insights and Interviews from The 2014 FIGT Conference and The Emotionally Resilient Expat are available at summertime publishing

Completing our group of writers are Alice Wu, Becky Matchullis and Nikki Kazimova.

If you’ve ever doubted the positive influence of art, you might wish to reconsider. I’m in Penang, Malaysia, where street art has helped revitalize and create a cool vibe for travellers and locals alike.

If you’ve ever doubted the positive influence of art, you might wish to reconsider. I’m in Penang, Malaysia, where street art has helped revitalize and create a cool vibe for travellers and locals alike. the murals. The vast array of them was a complete surprise. And I couldn’t have known how delightful and engaging they’d be.

the murals. The vast array of them was a complete surprise. And I couldn’t have known how delightful and engaging they’d be. We stopped at a popular mural where people waited patiently to pose on the bike while a young couple created their own ‘masterpiece’. They became the star attraction as we all took their photo and chatted amongst ourselves. It’s clear that street art encourages interaction.

We stopped at a popular mural where people waited patiently to pose on the bike while a young couple created their own ‘masterpiece’. They became the star attraction as we all took their photo and chatted amongst ourselves. It’s clear that street art encourages interaction. through this Unesco World Heritage Site. Named after George III, Penang was ceded to the British East India Company in 1786 by the Sultan of Kedah, in exchange for military protection from Siamese and Burmese armies. The golden age of Penang was soon ushered in with tin, rubber and shipping industries. Other Europeans followed the British, as well as Arabs, Armenians, Burmese, Thai, Japanese and Indians to name a few. The most prominent group were the Chinese and still today, Georgetown reflects the rich layers of culture that they and the other settling pioneers brought with them.

through this Unesco World Heritage Site. Named after George III, Penang was ceded to the British East India Company in 1786 by the Sultan of Kedah, in exchange for military protection from Siamese and Burmese armies. The golden age of Penang was soon ushered in with tin, rubber and shipping industries. Other Europeans followed the British, as well as Arabs, Armenians, Burmese, Thai, Japanese and Indians to name a few. The most prominent group were the Chinese and still today, Georgetown reflects the rich layers of culture that they and the other settling pioneers brought with them. narrow go-downs (warehouses), marvelled at colourful Chinese temples and admired statuesque Colonial-style buildings. Diverse peoples have given Georgetown its fascinating mix of culture and architecture. The street art is a modern extension.

narrow go-downs (warehouses), marvelled at colourful Chinese temples and admired statuesque Colonial-style buildings. Diverse peoples have given Georgetown its fascinating mix of culture and architecture. The street art is a modern extension.

Penang and decides to stay awhile. He does some busking and asks if he can paint something on one of the walls.”

Penang and decides to stay awhile. He does some busking and asks if he can paint something on one of the walls.” “Ernest is a celebrated muralist these days,” Geokling tells me as she scrolls on her phone to show me his latest installation in a Singaporean hotel.

“Ernest is a celebrated muralist these days,” Geokling tells me as she scrolls on her phone to show me his latest installation in a Singaporean hotel. opportunity, when a little luck changes a life. And for the local people and those who visit Penang, the street art is an endearing, welcome addition to the rich culture of Georgetown.

opportunity, when a little luck changes a life. And for the local people and those who visit Penang, the street art is an endearing, welcome addition to the rich culture of Georgetown. .”

.” And so I find myself in the trendy, impossibly long China House that I had been told I must visit. It comprises three heritage buildings linked by an open courtyard that houses a cafe, restaurant, wine bar, galleries and a stage. The atmosphere is indicative of a new direction in this centuries old trading settlement that cherishes the past, but knows it must also embrace change.

And so I find myself in the trendy, impossibly long China House that I had been told I must visit. It comprises three heritage buildings linked by an open courtyard that houses a cafe, restaurant, wine bar, galleries and a stage. The atmosphere is indicative of a new direction in this centuries old trading settlement that cherishes the past, but knows it must also embrace change.